This week: THE UNIVERSE AVENGES ITSELF ON ME FOR MY LACK OF ENTRIES.

This week: THE UNIVERSE AVENGES ITSELF ON ME FOR MY LACK OF ENTRIES.Hi folks,

Loads of content not generated by me this week, which is awesome, since typing is slightly awkward since I lopped the tips of my thumb and index finger off my left (thankfully non-dominant) hand. First time in what's been probably over 11 years straight of multiple-times daily knife use that I've cut myself with a knife I was using. And though there were extenuating circumstances, the fact is that knives are like wild animals- if one bites you, it's your fault. Ironically, it actually happened maybe two minutes tops after I was telling my girlfriend about the silly things I'd seen people do in knife safety training classes.

Anyway, getting on with it:

Here's a video of Erika Moen, Dylan Meconis, and Bill Mudron talking about the art and life issues of being a cartoonist. It is thick with insight and blue humor, my favorite combination. The title of the video will give you a pretty good idea if their humor is for you.

Here's a fantastic essay by Evan Dorkin about the issue of health insurance, specifically as it relates to cartoonists, and even more specifically as it relates to cartoonists living in NYC. Bonus for you NYC people: It lists specific resources that his wife spent a lot of time tracking down, and gives tips on how to best go about contacting them. Bonus bonus: It includes a link to a video interview by Time with my friend Julia Wertz.

Finally, I'll conclude with some real tool talk:

Comic Tools reader Reynold Kissling purchased some Rosemary brushes recently (remember my article about them?) and compared them to his trusty Winsor and Newton, and I'm sad to say that they really came out lacking. Perhaps as she's had to fill more orders her quality control has gone down, but in any event the reason I recommended them was that you could order them sight unseen and TRUST that they'd be great. It seems that this is no longer the case, and I therefore no longer recommend getting them, if buying them is going to be the same crapshoot every other brand is. Better to go to the store and actually try your brushes out. I have reformatted the impeccably thorough, well photographed, and rather Comic Tools-esque report he gave on his livejournal and pasted it below. His website is here. His book "Kingwood Himself" can be read in its entirety over at Top Shelf's webcomics page, Top Shelf 2.0, and he will be selling his new book "Pale Blue Dot" at the Stumptown Comics Fest next year. I thank him for bringing this issue to the attention of Comic Tools readers.

Rosemary & Co. Brushes Review

I've been inking predominantly with brushes now for several years, and have become....somewhat discretionary in my tastes (some would say obsessive). My number one tool, my excalibur if you will, has always been the Winsor & Newton Series 7 Kolinsky brush, size #2. Simply put, the brush is perfect. It has a huge variety of line weights, has excellent snap, and holds a preposterous amount of ink for its size. They say the tool doesn't make the man, but when it comes to inking, you NEED a tool that will give you complete control over your linemaking, and the Winsor & Newton #2 does the job. So what's the problem? Well, as I'm sure most of you know, Winsor & Newton's brushes have become steadily less reliable over the last few years. A W&N brush is expensive, and if the bristles are even just a little bit out of alignment, then the whole brush is worthless and you've just wasted your hard-earned money. Three out of the last four W&N brushes I bought have been duds (and I do the water-test at the store before I buy them). I'm sick of throwing away my money for worthless brushes, and for the past few months I've been searching for a comparable alternative. Enter Rosemary & Company. I heard about them from the blog Comic Tools (run by a guy even more obsessively anal than me), and after reading rave review after rave review, I took the plunge and ordered a Series 33 #2 and #0. Suffice to say, my expectations were high. They arrived yesterday, and I've had a good chance to test them out.

I decided to compare them side by side with my Winsor & Newton:

The first thing I noticed was that the Rosemary #2 is much thinner than the W&N #2. More on that later. Then I decided to compare the brushes dry, to see how the bristles fan out when not held together by moisture:

This was the first sign of trouble. With a brand new brush, you expect the bristles to fan out pretty evenly. Here you can see that on the Rosemary brushes several bristles are sticking out haphazardly, pointing in every direction. Here is a closeup of each brush's bristles, starting with the W&N #2:

At this point, I want to mention that my Winsor & Newton brush is over a year old. I've beat that thing to hell, leaving dried ink in the ferrule and dragging it across harsh paper, and yet its bristles are still more uniform than the brand new Rosemary brushes. You can plainly see that many of the bristles in the Rosemary brushes are not aligned. So how were they to ink with? Well, mostly it was frustrating. The #2 couldn't get a fine point, it didn't snap very well, and it did not retain very much ink. This is where its size comes in. As I mentioned earlier, the belly of the Rosemary #2 brush is much thinner than the belly of the W&N. The belly of a brush holds ink and helps provide the snap that is so crucial to making crisp lines. Even more frustrating was despite the fact that the Rosemary brush was thinner, it could not make thin lines like the W&N can. I found that I had to resort to using the #0 to make the same lines my W&N can easily handle by itself. Also, the brushes just felt weak. I had to apply more downward force to get variety out of the lines, and in those instances the entire brush bent with the curve all the way down to the ferrule, instead of just the tip. And lastly, the Rosemary brushes lost their point extremely easily. If they got the least bit dry or if I tried to take too sharp a corner, the tip would split and fork off, breaking the single line into two. Here's a portion of the panel I inked with the Rosemary brushes:

I know it doesn't look like I was experiencing the disaster I just described, but you can rest assured that I was fighting with these brushes the whole way. Last and probably least, the handle of the Rosemary brushes felt inferior to the W&N brush. I took a photo as evidence:

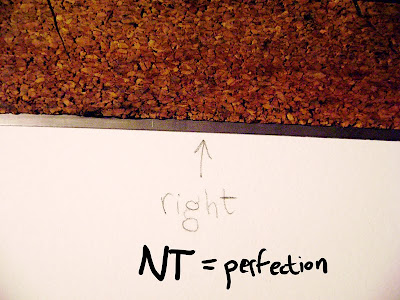

Take a look at the light reflecting off of the handles of each brush. On the left, the reflection coming of the W&N is smooth and regular all the way to the edges. Immediately to the right, the reflection is bumpy and irregular, especially near the edges. These reflections highlight the irregularity of either the wood of the handles or the paint applied to them. This is certainly nitpicking, but it does make a difference. I'd like to think that I am a scientific man, and that you wouldn't be satisfied with me simply describing the problems I had with these brushes, so I thought I would prove them empirically through a series of inking tests:

The first test consisted of me dipping the brushes fully (not to the ferrule of course) and then drawing a straight line continuously until they ran out of ink. As you can see, the W&N ran roughshod over the Rosemary #2, and the #0 could barely hang in there for three lines.

The first test consisted of me dipping the brushes fully (not to the ferrule of course) and then drawing a straight line continuously until they ran out of ink. As you can see, the W&N ran roughshod over the Rosemary #2, and the #0 could barely hang in there for three lines.

In this test, I simply followed a tight curve in a single stroke with each brush. Now this test probably reveals my weaknesses with inking more than anything else, but you can see that each brush did about the same. I would like to note, however, that the #0 forked out at the end of the line.

This last test is the most revealing. Here, I started a line with each brush at a certain thickness, then tested the limit for how thick and thin a line each could produce. As you can see, the W&N has an extreme capacity for variety of line weight, going from phat with a "ph" to supermodel-thin with no trouble and with me in complete control throughout. The Rosemary #2, however, can't even come close to reaching the same level of thickness, and you can see that the line already starts to break up before I even finish the first fat part. As you can see, I was able to get the Rosemary #2 down to the same thinness as the W&N, but not without losing the line entirely. I obviously am not in control of the brush at this point. The Rosemary #0 obviously can't keep up, and the brush is almost totally dry before I can even get to the second thickness test. The Winsor & Newton runs laps around the Rosemary brushes in this last round. So there you have it. The brand-spanking new Rosemary brushes, which came on the heels of rave reviews and high expectations, couldn't even stand up to an abused ink-clogged year-old Winsor & Newton brush. But really, there are no winners here. As long as Winsor & Newton brushes are going to be so inconsistent, we are going to be left with worthless brushes and empty wallets. The search for a better brush goes on...